As an editor, I hear a lot of questions from writers about this or that rule. It turns out a lot of people, even seasoned writers, have a lot of bad writing rules that trip them up unnecessarily.

It may or may not surprise you to learn that some of these bad writing rules have been around for a long time. Ever heard that you’re not supposed to end a sentence with a preposition? That can be traced to the 17th-century poet and critic John Dryden and probably has to do more with Latin grammar than how the English language makes sense.

(If you want to know, because Latin word order is more fluid than English, the placement of a preposition matters a lot; it has to be “positioned” pre-, or before, the noun.

Conversely, since English relies more on sentence order, it actually frees up the preposition to slip around a little and still make sense. For example, we can say, “In English, it doesn’t matter as much what position the preposition is in.”)

Sticky Bad Writing Rules

During my internet travels I encountered an interesting little case study of freshman composition students that illustrates this phenomenon.

The author of this study, Thomas Newkirk, assistant professor of English at the University of New Hampshire and the director of the New Hampshire Writing Program, identifies several common beliefs about writing.

See if any of these sound familiar to you:

- I shouldn’t be too personal/I should keep things objective.

- I shouldn’t mix personal experience with research.

- I don’t want to bore the reader with detail.

- I don’t like to revise/I can’t say it any other way.

As a writer and editor and former composition teacher, I can tell you I have seen all of these and all of them are problematic.

What struck me as interesting about Newkirk’s article was the date: 1981. These bad writing rules have stuck around for at least 40 years.

Where Do These Bad Rules Come From?

Newkirk offers several diagnoses of what was going on. First, he says, students get intimidated by putting words on the page, which feel “official” or like they should have extra validity.

Call it the threat of the written word. It tends to make people believe they need to imitate a presumed style that signals “professionalism” or “objectivity.”

Second, he suggests that writers write too much like they’re having a conversation.

But conversation is fluid and interactive and allows people to negotiate their understanding of subject and context and so on. Writing, by contrast, lacks that interaction and thus requires the author to supply extra context.

I call this the mind reading fallacy. It’s when the writer leaves things out that require the reader to read their mind to understand what they mean. That’s not writing, that’s telepathy.

Third, Newkirk says students confuse words and their referents and believe that they are the same thing. What he means is that writers think there is only one way to communicate their idea and so once they have put words down they can’t change those words without changing the idea.

This, obviously, stifles revision. In my experience, and in Newkirk’s case study, this is really about believing that the words you write “spontaneously” are somehow sacrosanct because they express something important to you.

I call it the myth of the silver tongue.

What Are the Good Rules, Then?

As your therapist will tell you, it’s not enough to know you hold a bad belief. You need to replace false beliefs with true ones. So, what are better rules than the bad ones above?

1. Genre is a game, not a prison.

Never sacrifice clarity to some notion of complexity or formality. Yes, there are genre rules, but genre is more like a game than a prison.

That is, it’s not about demanding conformity but about helping you know what is in bounds and out of bounds and what success looks like.

2. Ask, “What does the reader need to know?”

To avoid requiring mind reading, you need to think about your reader. So, ask what the reader knows based on what you’ve written and what they still need to know. Then figure out how to communicate that in your respective genre.

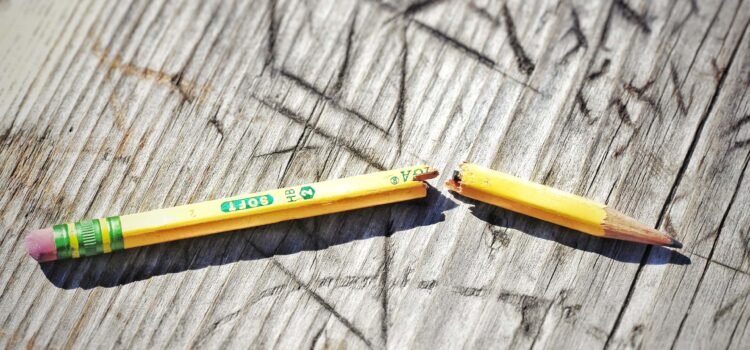

3. Writing is a form of thinking. Writing is revision.

Sorry, honey, but not everything you say is brilliant. It doesn’t have to be. Writing it down helps you see what makes sense and what doesn’t. Because you are writing for an audience, you have to expect that you will need to revise as you clarify and refine your ideas.

That’s okay. Trust the process.

There are so many ways to pick up bad ideas about writing rules that there’s really no point in feeling embarrassed about it. You write, you learn, you write some more.

And if you need help whipping your writing into shape from someone who knows the rules and when to break them, get in touch with me!

Source:

Thomas Newkirk, “Barriers to Revision,” The Journal of Basic Writing 3:3 (Fall/Winter 1981): 50–61. DOI: 10.37514/JBW-J.1981.3.3.06.

Photo by Joshua Hoehne on Unsplash